In Which The Gorilla Talks About Art

I just can't make up my mind. Are the Americans in Iraq Stupid and Evil? Or are they Evil and Stupid? Irrespective of which they are isn't nice to know that at their top ranks that there's a sensitive soul, an art critic no less. Major General William Caldwell appreciates art. Doesn't that make you feel all warm inside? Let's talk about art. First there's this:

There's a fuller version of the story on Time.com here. Cardona got a wrist slap for mistreating what the US military, reflecting the society from which it springs regard as subhumans untermenschen, "sand niggers" who "only understand force." Declan did a posting on this topic back in July "The only thing these sand niggers understand is force and I'm about to introduce them to it" Well of course if they're only sand niggers then they're subjects, or perhaps objects, not people, just raw material. Raw material for artists. Artists such as Sgt. Santos A. Cardona. Remember this?

Artistic isn't it? Cardona got off because his lawyers argued, truthfully. that he was doing what his superiors wanted him to do. I rather suspect Cardona got off because during the plea bargain negotiations his lawyers threatened to give the names, ranks, and serial numbers, of the people who ordered the barbaric behaviour in which he and his fellow American soldiers engaged in Abu Ghraib and are still engaging in other prison camps in Iraq. Such as Camp Bucca. Cardona's superiors (and their superiors in the White House and the Pentagon) based their belief in the efficacy of such filth upon that racist tract "The Arab Mind" by Raphael Patai. No I'm not going to link to it I've more respect for my readers than that. Patai argued that you control an Arab by humiliating him, by terrifying him, by torturing him, but most of all by humiliating him. And it's true, you can control an Arab, or any other human by such methods. For a while. A short while. What Patai who was racist to the core didn't bother to mention is that Arab societies are honour based societies. Honour is important, it's the sine qua non. If you take away an Arab's honour by humiliation and degradation then he and his entire extended family share in the loss of honour. And every single one of them is duty bound to regain their honour by avenging the insult. Is Torture Art?Oh yes, it most assuredly is. It's a black art inspired by evil. It's a black art engaged in by evil people. So we have one type of artist returning to his studio. One wonders what he'll produce next. Can we expect to see reports in the art journals of sightings of "school of Cardona" works? Quite probably. It wouldn't surprise me even slightly. I have reached the point where there is no evil I will not believe of the American forces in Iraq. And I have reached the point where flatly against my all my instincts and training I now assume that every American in Iraq accused of barbarity is guilty until proven innocent. But I digress. Let's continue our exploration of art shall we?

Oh how nice. Isn't that just special. The carnage, the slaughter, the rampant evil unleashed by America upon the men, women, and above all the children of Iraq is a "work of art" in progress. Performance art perhaps. Or perhaps it's the auditory experience. How would that go? We'll have to find someone to orchestrate the sound of weeping parents and the shrieks of agonised children for Major General William Caldwell. Nothing but the best for Major General William Caldwell and his fellow aesthetes will do. Why should Major General William Caldwell and his fellow aesthetes confine themselves to just the plastic arts when the full range is available to them? There's certainly enough skulls around to inspire a sculpture. Hmmmmmm ..... Maybe not - it's been done before:

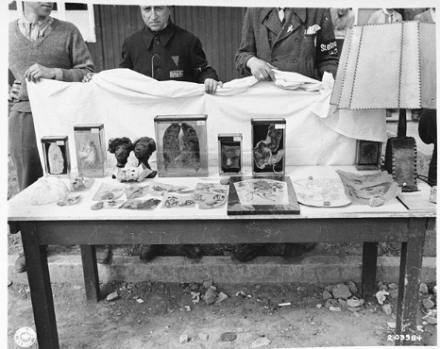

I'm really not qualified to talk about art such as this. I can't appreciate it. I'm not Major General William Caldwell and I'm not Ilse Koch either.

So I'm going to stop talking about aesthetics and art. I'm going to stop before I get sick. Koch collected and commissioned "objets d'art" made from the bodies of concentration camp victims - such as those you see in the photo above. In particular she liked to collect "interesting" tattoos - flayed from murdered inmates' bodies. And those helpful Iraqis have already made a start on providing the raw material for a new art collection for a new generation of art connoisseurs: These tattoos aren't artful - they help identify Iraq's deadBy Nancy A. Youssef BAGHDAD, Iraq - Ali Abbas decided that his upper right thigh was the best place for a tattoo because no one gets tortured there.

He'd seen hundred of bodies in the city morgue and dozens of hospitals during his 18-day search for his missing uncle. He'd seen drill marks in swollen, often unrecognizable heads, slash marks across necks, bullet holes in backs, abdomens and swollen hands. He'd seen bodies that had been thrown into the river, so swollen they'd barely looked human. But by and large, the thighs had been intact. So that's where he decided to have his name, address and phone number tattooed, in case the day comes when someone is searching for his body. Tattoos are considered a sin in Islam, which holds that believers shouldn't deface their bodies. And tattoo shops are difficult to find in Baghdad. They're often in the basements of more reputable shops But at least some tattoo shops are seeing more and more Iraqis who, like Abbas, are willing to risk offending Islam to ease their families' grief in the event of their deaths. The owner of one tattoo shop in central Baghdad admitted that he'd done such tattoos, but said he didn't want to talk about it for fear that he'd be killed. That some Muslims are getting tattoos is an intimate reflection of national chaos, and an outward symbol of the inner turmoil the chaos has created. There's nothing artful about these tattoos. The branding has the efficient look of a business card, written in clear, bland type. "This is our life now," Abbas said as he explained why he doesn't think that having a tattoo makes him a bad Shiite. "I think this is the best way for my family to recognize me. Everyone knows in my family that I have it: my mother, my brother, my wife." There's no way to know how many Iraqis have made Abbas' choice. Officials at Baghdad's morgue say they've used tattoos to identify bodies, but never one with a name and address. Police officers told McClatchy Newspapers that they've encountered bodies with names and phone numbers tattooed on them. They've called the numbers and let the families pick up the bodies instead of taking them to the morgue. Jalal Ahmed, a police officer in southern Baghdad, said residents called his station three months ago because they'd found a body in the street. Fearful that a militia would kill them for approaching the body, they put off calling until dogs began eating it. Ahmed found the tattoo: "The dogs had torn part of the clothes, and I saw a tattoo with his full name, on the upper part of one of his arms. He was Atheer Mohammad," Ahmed said. "We asked around, and nobody knew him. He was from a different neighborhood, so we called" the number. Whatever the extent of its use, the decision to tattoo reflects the country's level of violence. It seems that anyone can be kidnapped and killed for any reason. Abbas realized how possible that was a few days before he got the tattoo. "I saw two vehicles, and they took five people out and shot them in front of my eyes," he recalled. "I was about to drive away. They stared at me, and I thought they were going to shoot me too, but they drove away. And I thought, `What if I were one of the five people?' Nobody knows them. Everyone is scared. No one will help them." There are few Iraqis who haven't had to search for family members who've been kidnapped, tortured and tossed in another neighborhood. Or who know of someone killed by a homemade bomb, a shooting or a car bombing. Or taken on the way home from work only to show up at the morgue days later. Or discovered by American soldiers in makeshift graves. A family's search can take days, and frequently it doesn't turn up a body. The idea of not properly burying a loved one is almost as torturous to a pious Muslim as not knowing how or why the person died. About 100 bodies are found each day nationwide. Most people have been taken from one neighborhood and killed in another. In Baghdad, the morgue has become a Shiite-dominated wing of the Ministry of Health, and some Sunni Muslims dread going there to pick up loved ones for fear they'll be kidnapped while they're there. Some police officers are afraid to approach bodies in their communities, fearing that they've been booby-trapped. Moreover, in the absence of an able nonsectarian security force, many assume that the government can't defend them from the raging ethnic and religious violence. In some cases, they charge that the government is contributing to it. Abbas, 24, who cuts meat off kabob racks for a living, lives in Kefah, a poorer western Baghdad neighborhood. He has a car, and his neighbors often ask him where he got the money to purchase one. He worries that the decision to kill could be fickle. "They ask: How did I get it? And they don't know that I work hard. Maybe they will kill me for this car." Abbas' uncle, Hussein Ali Jassim, disappeared four months ago after leaving his shift at a police station in western Baghdad. The family waited for the ransom call, and when it didn't come, Abbas searched for him, first at the hospitals, where he asked to see the refrigerated bodies, then twice at the morgue. When he didn't find him, "I figured he was still being tortured." On his third morgue visit, he saw a photo of a swollen face that he thought might be his uncle's. But he wasn't sure until he saw the tattoo on the right arm, a heart surrounded by his uncle's and aunt's initials. Abbas was shaken by his uncle's death. He decided to brand himself when a friend, policeman Ahmad Ali, 23, showed him his tattoo. Ali said he got a tattoo with his name, address and phone number because he walked by a wall in his precinct every day showing the faces of the 60 officers who'd died violently, many of them after they'd been kidnapped. Now officers share with one another where they can get tattoos. "Getting tattoos has become very popular among policemen and national guards," Ali said. "We're kidnapped all the time. This is the only way we will be returned home. We face death every day." Abbas didn't consult anyone before he got his tattoo, and his wife and mother cried when they saw it. He said he planned to have his two younger brothers tattooed when they're older. "My mother was blaming me: `Why are you bringing death to yourself?' I told her it was just a precaution," Abbas said. "I don't assume I will die. Ultimately, it's up to God whether I live or die." McClatchy Newspapers special correspondent Zaineb Obeid contributed to this report from Baghdad. Hmmmm .... Just numbers, no interesting pictures, how disappointing that must be for the art-loving Major General William Caldwell. Still to paraphrase his boss "You build your art collection with the tattoos you have, not the tattoos you might want or wish to have at a later time." markfromireland Update: Here's the direct link to Caldwell's press conference. You need to scroll down a bit. Hat tip Bernhard of Moon of Alabama - mfi. |